Teens’ Excessive Internet Use Not Always Problematic

Excessive internet use might not necessarily hurt teens’ development depending on the type of internet addiction, a study in Computers in Human Behavior shows. The study identified four profiles of internet-addicted teens, and only two of these profiles are potentially problematic.

Take aways

- Four distinct profiles of internet-addicted teens:

- Juggling it all: teens who balance their high internet use with a rich offline social life;

- Coming full cycle: teens who recognize their excessive internet use and self-correct it by modifying their patterns of use;

- Stuck online: teens who are trapped on the internet because of a lack of self-regulation and experience reduced offline contacts;

- Killing boredom: teens who use the internet to escape negative emotions like boredom and also disengage from offline activities.

- The internet use of teens who “juggle it all” and “come full cycle” can be seen as adaptive, whereas the patterns of use of teens who are “stuck online” and “kill boredom” are more problematic and need intervening.

- Clinicians can use these profiles to deliver interventions more personally and for parents the profiles can increase awareness for teens’ motives to go online and aid the promotion of adaptive internet use (e.g., through supporting and enriching offline activities).

Study information

The question?

Can we identify distinct profiles of internet use patterns among teens with internet addiction and can these profiles help distinguish between adaptive and problematic internet users?

Who?

72 teens from Greece (27.8%), Iceland (27.8%), Poland (27.8%), and Spain (16.6%) who were moderately or highly problematic internet users (mean age: 15.7 years, 56.5% boys)

Where?

Greece, Iceland, Poland, and Spain

How?

The study was part of a project carried out across seven European countries that investigated the experiences of teens with internet addiction. Participants were recruited through their secondary schools. All teens between 14 and 17 years old with self-reported signs of internet addiction (as indicated by an internet addiction test they filled out) were eligible to participate. Teens were separately interviewed by trained psychologists and sociologists. Specifically, they were probed to reflect on their patterns of internet use, including motives, habits, and consequences as well as (the comparison between their online and) their offline lives. The researchers then used teens’ answers to identify distinct profiles of excessive internet users based on three processes: whether and how teens (1) satisfied needs between online and offline contexts, (2) experienced personal gains and losses, and (3) could self-regulate their internet use.

Facts and findings

- All teens said they used internet very frequently through various online activities (primarily social media), which, according to the authors, indicated a developmental yearning for seeking information and social contact.

- Four distinct profiles could be identified, ranging from more adaptive to more problematic:

- Juggling it all: teens in this profile were high internet users that structured their use in such a way that they only experienced minor negative consequences (e.g., occasionally experiencing sleep deprivation or neglecting homework). These teens had vivid offline social lives and used the internet as a complementary medium to manage their real life contacts. They did not over-value online activities because they did not solely rely on them;

- Coming full cycle: this profile consisted of teens who said they previously overused the internet but now modified (or were modifying) their use. These teens reported inefficient self-control but were increasingly able to see its consequences. From the stories of the teens two “routes to change” became clear. Some teens experienced negative consequences, such as social estrangement or deteriorating grades, which triggered them to change their internet use (i.e., self-correction). Other teens, at some point, just had enough of the online activities they previously enjoyed and reduced their excessive internet use (i.e., saturation);

- Stuck online: teens in this profile described themselves as being hooked on the internet as a result of over-reliance on the medium and lacking self-regulation. As a result, they neglected real life tasks and contacts and their offline functioning became impaired. They were stuck online because their internet use was positively reinforced by empowering online experiences (e.g., potentially receiving a response to a message on social media is intrinsically rewarding);

- Killing boredom: this profile included teens who used the internet excessively to escape negative emotions. Whereas all teens indicated boredom as a reason to go online, teens in this profile also described to escape from other negative emotions like emptiness or sadness. These teens seemed to be disengaged from their real lives, probably due to poor psychosocial functioning. For them, the internet was an easy alternative solution to get away from negative thoughts and feelings, suggesting a limited ability to cope with emotions.

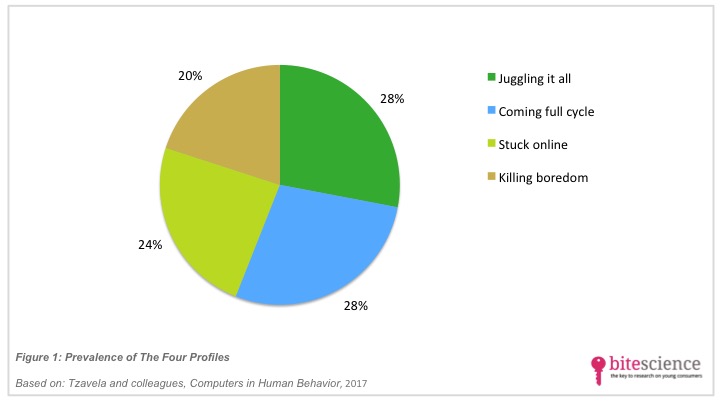

- The adaptive profiles (juggling it all and coming full cycle) were more prevalent than the problematic profiles (stuck online and killing boredom; see Figure 1).

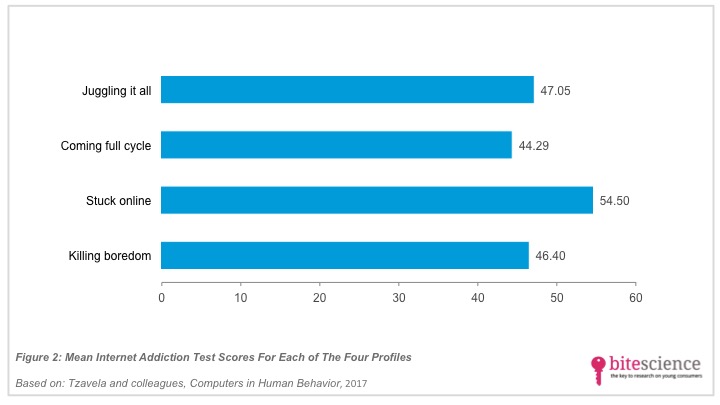

- Interestingly, the internet addiction test scores did not fully correspond with the four profiles (see Figure 2).

- Although teens in one of the problematic profiles (stuck online) scored highest on the test, teens in the least problematic profile (juggling it all) scored higher than teens in the most problematic profile (killing boredom). As there were overall variations in internet addiction test scores within each of the profiles, the authors suggested that such tests might not fully capture the nature and sources of teens’ problematic internet use.

- Critical note: This study was based on self-reported, retrospective data as teens were asked to reflect on their past internet use, and might therefore be less reliable. Also, although the participants in the study came from different countries, no attention was paid to differences in culture of the teens.